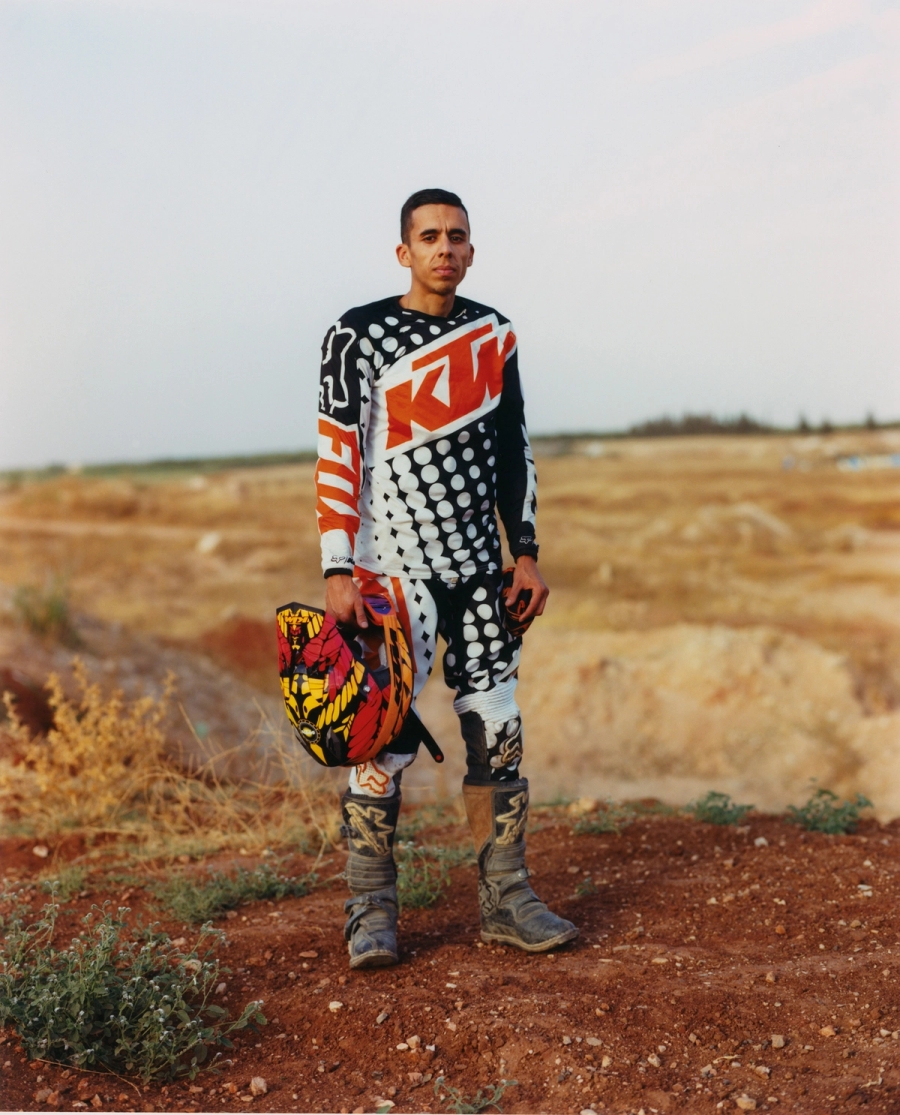

MOROCCO by Ilyes Griyeb

PHOTOGRAPHY Ilyes Griyeb

French-Moroccan photographer Ilyes Griyeb’s first book, ‘Morocco,’ is a compilation of photographs that span over the past six years, all of which play with the boundaries between fact and fiction, while putting history and context at the forefront. Drawing on his “dual identity,” Ilyes’ “half-staged” portraits locate the future directly within the rural.

In 2013, you began this project to tell the stories of those around you—which then grew into Morocco, a “moving portrait” of Morocco, six years later. How is photography a tool with which to take control of popular representations and images? It seemed like a very organic process.

Popular representations, most of the time, are done by tourists—people taking photographs who don’t have much knowledge of the country, and who don’t know its full story; it’s not necessarily the truth. With this project, it came about very organically because my family and I are from Morocco, and it’s my culture. When I began photography, I started taking portraits of my family and my surroundings. So, my understanding of the country is very personal

What is it about Meknès that made you want to document the ordinary and everyday aspects of rural life?

In Morocco, the landscape is mostly rural. To tell the truth about Morocco, my project had to focus on these rural areas. On the contrary, when these images of rural Morocco do circulate in the mainstream, it leads to myth-making: they’re inscribed with narratives about the “authenticity” of Moroccan culture, and they’re often bound to the past, instead of Morocco’s present. I wanted to break away from this narrative and spotlight how Morocco exists very much in the present. I wanted to show it in all its richness and complexity. I would describe the book as a “backstage shoot” of Morocco.

How did you bring your different perspectives and dual identity—from your experience of growing up between France and Morocco—to the forefront of this project?

This project can be described through the lens of W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept and experience of “double consciousness” which is “the sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” (1903). This concept of double consciousness gave me a lot of perspective—this notion helped me gain a deeper understanding of my parents, my cousins, and also myself. This concept is present throughout all of images—it’s like I have a foot in the past and one in the future. Meaning, when I go to Morocco, it’s like I’m the past, and my parents are the future: the dreams and aspirations they brought with them when they came to France. This is how I see Morocco because it’s who I am; understanding them is about understanding myself, too. With photography, I can balance the reality between them—both familiarity and distance.

How does this book align with other projects you’ve been working on—with the collective, NAAR, for example? I.e. using your access to the art world to tell different stories than the ones represented in the global imaginary?

Well, NAAR is a continuation of what I do in photography—they are interconnected. I began the collective with my friend Mohamed (Sqalli), and we wanted to spotlight how artists in Morocco, and other locations, do not have access to the same opportunities, even though Morocco’s cultural influence is significant in popular culture. Although many artists are incredibly talented, it isn’t easy to evolve outside of Morocco. What’s interesting, for example, is that a lot of rappers from France will travel to Morocco, and work with different artists to make tracks and albums, buying the melodies from Moroccan artists—they sell their flow, which is called a “top line.”

Mohamed and I wanted to reclaim the aesthetics of international artists, so we created SAFAR—meaning travel in Arabic—an album that highlighted the work of a new generation of Moroccan rappers. We began the project in France, and then we rented a villa in Casablanca. The only rule was that: we asked each artist to record one track for us—at the end of the residence, anything they produced was their own, but we would take one track from them. There were 38 different artists, and we signed the album with Def Jam Records. More importantly, it is an album made by a generation of artists that “no know borders, see no class, and consider talent as a sole truth.”

How do you use staged portraits, documentary photography, and landscapes to contrast global representations of Morocco?

Well, the portraits are not totally staged; I would say they are “half-staged.” The photographs came out of actually spending time with the people I was shooting; I would hang out with them for a day, or an afternoon. It was a very organic and spontaneous process. If the photos do appear to be staged, I can ask them to re-do something they were already doing on their own, but I would never ask them to do something for me.

What have you learned during this process?

I learned that the dream of one person, can be the nightmare of another’s; their frustration can also be someone’s relief. More importantly, I realized that everything is a question of position and situation—where you are can shape who you are.