Louise Bourgeois' Lairs at Tarmak22 by Camila McHugh

Louise Bourgois, The Heart Has Its Reasons, Hauser & Wirth at Tarmak22.

"The lair is a protected place you can enter to take refuge. And it has a back door through which you can escape. Otherwise it's not a lair. A lair is not a trap" - Louise Bourgeois

2020 introduced a taxonomy for our contemporary confinement, as the likes of quarantine, self-isolation and social distancing became common parlance. It’s 2021 and a lot of the world is still staying home in accordance with a shuffle of state and self-imposed restrictions, so the house continues to assume a range of titles as well. This is, of course, essentially to state the obvious—this is the way things are—but as Louise Bourgeois knew well, careful consideration of how spaces constrain and contain bodies clues us in to what it means to be human. The question of enclosure comes to the fore in The Heart Has Its Reasons at Tarmak22 in Gstaad, which spans nearly the seven decades of Louise Bourgeois’ monumental career in works across mediums that return to motifs of the embrace, clasped hands or the spiral.

Maybe it’s because life has grown so lair-like lately, but the two works titled as such are where I linger. A lead, pendular sculpture hanging against the dramatic windowed wall, Lair (1986-2000) is framed by a wintery forest backdrop. Its surface is uneven, marked with compressions like traces of touch. Bourgeois made the work in rubber in 1986, experimenting with the lead cast for years until she finally found the right fabricator and devised a successful method to complete the work in 2000.

Sloping indents rut into its sides like a path worn by habitual passage and a small, rectangular opening cuts through the work, offering a way out. This tunnel invites you to crouch down, peering through to catch a different glimpse of the Alpine landscape on the other side.

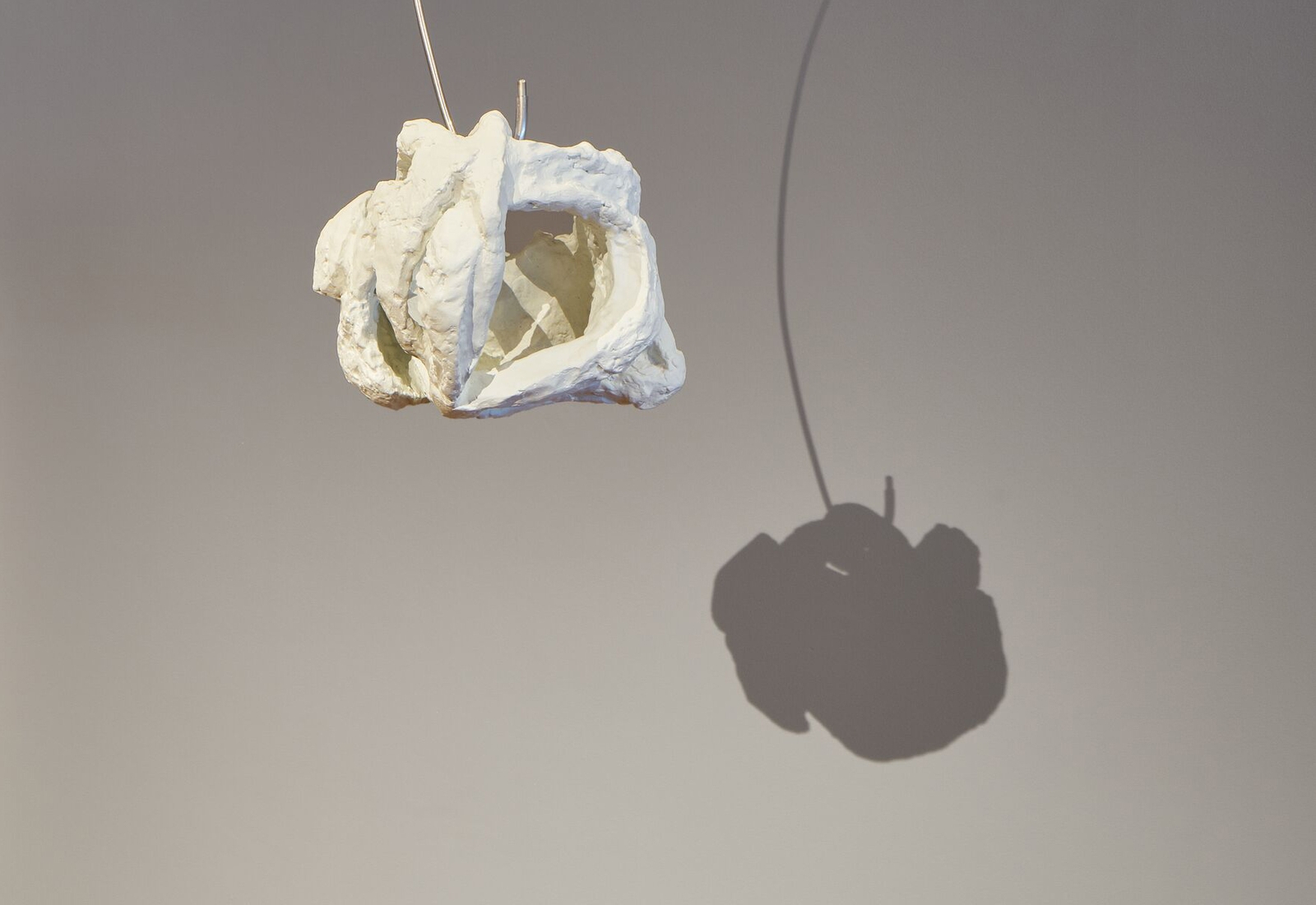

The second Lair (1962) is a smaller work about the size of a head: its raw forms cluster into a structure that resembles an opening cocoon.

The sculpture’s rough, white-painted bronze looks like plaster, accentuating the germinal nature of the shape. The motif of the lair remained decidedly unresolved within Bourgeois’ oeuvre, as she drew out something undetermined in these abstracted dens in turn. Adjacent to her investigation into the figure of the home, the lair would also instigate her Cells Series: the architectural, psychological spaces that absorbed her practice for almost two decades were initiated with the 1986 sculptural environment Articulated Lair.

Bourgeois’ work emerges from the friction in the two-sided nature of things: the tension in the strange coexistence of being cradled and smothered, held and trapped. Accordingly, the lair is characterized by refuge and escape, a haven for a kind of precarious freedom. She finds the visual language for this shelter in the natural world, drawing on the shape of a nest or a hive. This is a sketch for an understanding of wholeness constituted, rather than threatened, by fissures or gaping holes.

There’s a solitude implicit in a sanctuary that is reliant on a backdoor, intimating a sense of belonging found outside of relationships with others, and via detachment instead.

Perhaps that is why the way these works remain somehow unsettled, like a hypothesis that Bourgeois let dangle in rubber for many years, returning insistently to the many dimensions of the relationship with the Other instead. Ultimately, it seems, she was uninterested in taking that back door.

Founded in 2019 by Antonia Crespi and Tatiana de Pahlen, Tarmak22 exists to breathe life into the cultural landscape of the Swiss Alps. Located directly on the site of the Gstaad-Saanen airport, the galley takes its name from the runway that it overlooks.