Glass Cypress: a refreshing anomaly, between fashion and hospitality

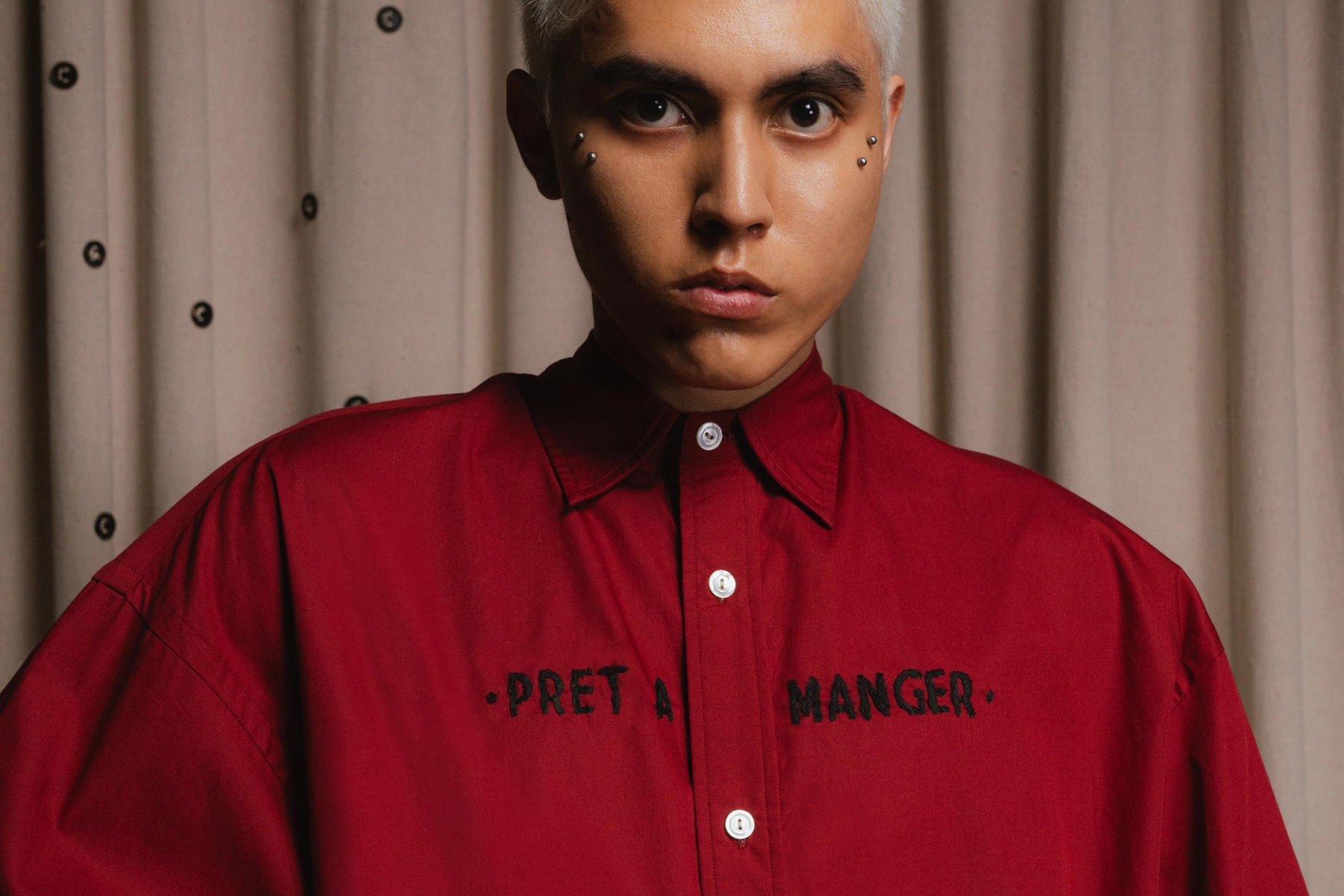

Glass Cypress (founded in Houston, Texas) exists in a captivating space of ambiguity—crafting products that feel both timeless and elusive, evoking a nostalgic yet unplaceable familiarity. In this interview, we sit down with Saber Ahmed, the creative force behind Glass Cypress, to dive into the essence of their journey. From blending fashion and hospitality to navigating the cultural nuances of Houston, Saber shares insights on balancing intuition with industry demands, embracing creative risks, and the ever-evolving pursuit of authenticity.

Novembre: Is it possible to describe the world of Glass Cypress in one sentence?

Saber Ahmed: Glass Cypress exists in a space of ambiguity—creating products that feel like they come from "nowhere", difficult to trace in inspiration or motive, yet evoking a nostalgic and strangely familiar feeling.

Do you remember when the vision of incorporating hospitality into your universe started to become more clear?

When we first opened our store—two years before stepping into hospitality—we had what is now our omakase bar set up as a cocktail bar, offering complimentary craft cocktails to customers. Southern hospitality has always been embedded in our DNA, but the idea of a full-fledged hospitality group was never a calculated decision. It evolved naturally, almost unintentionally.

Being based in Houston, do you rely on local mentors, friends, or institutions for input? How has the city’s (or Texas state’s) environment shaped your approach?

I never intentionally set out to design through the lens of my upbringing/Houston, but I suppose you can never really escape where you come from.

When people see our collections, they sometimes reference an “Old Western” or Texan influence, which likely stems from the environment I grew up in—the climate, the culture, the sensibilities.

That said, I try not to take direct input from others when designing; intuition is deeply personal, shaped by influences most people can’t articulate or relate to.

Is it hard finding an equilibrium between listening to your own voice(s) and taking advice from people in the industry — both in fashion and hospitality?

This is the fundamental challenge of building a brand. Growth inevitably demands balancing creative intuition with business logic. Authenticity comes from a feeling—an instinct. I trust mine, and I rarely go against it.

Which creative movements or communities worldwide inspire you most right now?

I’m moved by creative individuals in certain authentic moments: there’s something raw about live artist performances that stays with me through the design process.

It’s not about what an artist is wearing but the energy they radiate—the uninhibited freedom of expression.

For example, recently I found myself fixated on Cyndi Lauper’s live performance of Girls Just Wanna Have Fun on the Tonight Show—not for the clothes, but for the way she embodies a pure, unfiltered presence

How does your curiosity of the world change with time, or with each collection that you realise? (If it does...)

Intuition is constantly evolving through experience—travel, conversations, other designers’ work, the collective movement of fashion as an industry. But at the core, the vision remains intact. That’s the beauty of creative work: we’re all progressing forward, feeding off each other’s ideas, yet the responsibility remains to maintain an undiluted perspective and resist falling into groupthink.

How does your creation process differ for fashion versus hospitality? (I.e. How to start a collection VS a seasonal menu…)

Or do you go into it not really knowing? How much unknown is there, in general?

My role in hospitality leans more toward business strategy and creative marketing direction, whereas in fashion, I’m deeply involved in the design process. That said, all three aspects—finance, marketing, and creative design—require a similar mindset: independent thinking, leveraging the strengths of others, and introducing novel concepts. The unknown is an essential part of creativity; it keeps things exciting.

Our chefs are just as experimental as we are in fashion, always pushing boundaries to keep things fresh and innovative, much like how we approach each collection.

How do you balance creating and discovering how to position your brand, with the exhaustion that sometimes comes with developing your own business, especially in the US?

Working on the business versus in the business is an ongoing challenge. Positioning the brand is tricky because, as a creative, your perspective is always evolving—you just hope your original audience grows with you. Otherwise, you’re caught in the exhausting cycle of constantly chasing a new clientele.

Browsing through your garments, a certain lightheartedness comes to mind, combined with extreme attention to detail: It feels like playing around with the tools is really an experimental way of being curious about how the form can tell a story. Thoughts?

Effortlessness is central to Glass Cypress. Clothing should never feel overly labored in its wear or its styling—vanity and fashion can’t coexist. That’s where the lightheartedness comes from. The attention to detail, on the other hand, is a byproduct of craftsmanship—our artisans’ approach is meticulous, drawing from native Bangladeshi techniques that are embedded in the DNA of our pieces.

In my experience, the work is ready when it’s ready and you’ll know when it’s ready, but you also have to be ready. How is that process or you – when is the work "done" (if ever)?

There’s a paradox in it—the final product should exude effortlessness, but getting there requires real effort. About 75% of my designs make it through, guided purely by instinct.

I start designing the day after our showroom closes and finish the day before the next one opens. Whatever comes out in between, I accept as the collection’s fate.

With your practice spanning multiple avenues, how would you define success and how do you define failure in the realm of your creative work?

Success, to me, is about preserving the purity of the creative vision—how much of the original intent makes it through the hurdles of business, logistics, and financial constraints. Barriers are inevitable in capitalism, but success is navigating them while keeping the essence intact. Failure is when the work feels compromised, when intuition signals something is off. And intuition never lies.

Do you feel that people generally “get” what you’re doing, or would you like your work to be more widely understood?

I would love for the brand to be more widely understood, but true understanding takes time—even for me. A brand is like a child; it takes years to fully grasp its identity, both as its creator and as its audience.

Looking back, what do you wish someone had told you when you were just starting out on this journey?

I wish I had trusted my creative instincts in every aspect of the brand from the start—not just in designing clothes, but in everything from content creation to social media. I’ve always valued collaboration, but I’ve learned that leaning into the purity of the creative vision yields the strongest results. That’s something I prioritize now more than ever.